Josh Niemtzow, Law & Public Policy Scholar, JD Anticipated May 2021

When describing the changing character of our favorite cities, gentrification is often identified as the culprit. But what does gentrification actually mean?

Gentrification involves developers rebuilding homes and businesses in a deteriorating area, which then attracts more affluent residents, resulting in a displacement of poorer residents.

But it is not all bad: a little development in an underdeveloped area can increase amenities for existing residents. However, cities must be prepared to mitigate its negative effects, such as the loss in affordable housing stock and the increase in housing segregation.

A 2019 report from a DC-based policy group, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, concluded that Philadelphia is one of the most gentrifying cities in the United States. It found that over a thirteen-year period, Philadelphia had the fourth highest number of census tracts become gentrified, trailing only Los Angeles, Washington D.C., and New York City.

Philadelphia has three tools to respond to displacement: land, money, and policy incentives.

Philadelphia’s Land Bank conveys City-owned land at a reduced rate to housing developers who promise a fixed percentage of affordable units in their new housing developments.

Philadelphia’s Housing Trust Fund spends City funds to promote affordable housing production, existing housing preservation, promote homeownership, help meet rental obligations, and assist in making houses habitable for vulnerable populations. In 2016 alone, the Housing Trust Fund’s financial contributions assisted 13,823 households.

Finally, at the end of the 2018 legislative session, City Council created an incentive-based Inclusionary Zoning program. The “mixed-income housing bonus” allows developers of new multifamily residences to take advantage of floor area, building height, and housing unit density bonuses in exchange for providing 10% of units in a development at an affordable rate, or by making an in-lieu payment to the Housing Trust Fund. Inclusionary Zoning programs are widespread across the nation’s cities and affluent counties. They allow municipalities to incentivize the market to create affordable housing on its own.

Proponents of inclusionary zoning were relieved to have passed something, since the bill’s lead sponsor, Councilwoman Quiñones-Sánchez had been pushing for inclusionary zoning since the prior session. The Building Industry Association was also relieved, since it succeeded in getting the proposal to be voluntary rather than mandatory (the latter of which Councilwoman Quiñones-Sánchez preferred). Not all were pleased. A member of a concerned citizens’ group exclaimed that she and others who wanted mandatory zoning had been “bamboozled.”

Though the program has had some tentative success thus far, its impact is small. Nine months into the program, only twelve projects had expressed an interest in utilizing the program, and because nine of the projects had announced their intention to pay into the Fund, rather than provide on-site affordable housing, the potential for mixed-income communities is missed.

While Philadelphia’s Inclusionary Zoning policy was undoubtedly a carefully crafted compromise, and recognizing that the program is only a year old, several improvements could be made to increase the impact of the program and to support the broader goals of alleviating Philadelphia’s affordable housing needs.

Make Inclusionary Zoning mandatory for developers that take advantage of a certain level of public financing assistance

The Inclusionary Zoning program makes subsidized developers ineligible for bonuses. Not only should they be ineligible for bonuses, but developers who receive a certain amount of subsidies or tax incentives from the City should be required to contribute to Philadelphia’s affordable housing needs.

Treating developers who receive public financing assistance differently under an Inclusionary Zoning program is not a novel concept. Chicago’s mandatory Inclusionary Zoning program imposes heightened affordability requirements if a development receives tax incentives, while Detroit imposes heightened requirements if developments are subsidized with over $500,000 in city or federal funds.

Increase commercial participation in funding the Trust Fund

The program makes eligible only zoning designations that permit household living. But this is preventing the program from raising more money for the Housing Trust Fund, which lacks a robust permanent funding source.

Industrial Commercial Mixed-Use (ICMX) zoned properties, which accommodate commercial and low-impact industrial uses, and Auto-Oriented Commercial zoned properties, (CA) which are auto-accessible shopping centers, could similarly receive bonuses without being disruptive on the community. All sorts of businesses, including restaurants, markets, and medical practices can utilize land zoned under these designations.

Preference existing community in on-site affordable units

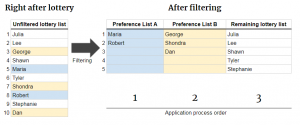

Preserving existing community ties is a crucial part of mitigating the effects of gentrification. A stronger advertising requirement or a lottery system that preferences existing residents in awarding on-site affordable units could serve these goals. Current law does not explicitly include any of these options.

For example, San Francisco’s affordable unit preference policy advantages previously displaced residents, community members, and those who already live or work in San Francisco.

Increase opportunities for developers to more directly contribute to affordable housing needs

Current law disfavors off-site housing production as a compliance option for the affordability requirement. Thus, developers have an all-or-nothing choice of paying into the Fund or providing on-site housing. More compliance options such as more explicitly allowing off-site housing or preserving, improving, or increasing the affordability of developers’ existing stock, should be considered, since comprehensive affordable housing policy is effectuated in a number of different ways.

You must be logged in to post a comment.