Hanna Pfeiffer, JD Anticipated May 2024, Law & Public Policy Scholar

The shipping sector accounts for 2–3% of global carbon emissions or about 1,076 million metric tons of CO2 annually. To put it into perspective, this is roughly equivalent to Japan’s yearly carbon emissions. CO2 is not the only worrying emission that comes from large merchant ships. With massive engines that can burn fuel at high temperatures, large ships use the cheapest, dirtiest fuel from an oil refinery: fuel oil. Fuel oil contains significantly more sulfur and heavy metals than other fossil fuels do. When burned, the sulfur becomes sulfur dioxide, which can harm the lungs, cloud the air with particulate matter, damage plants, and cause acid rain. Furthermore, many ships dump their spent fuel in the form of “oily bilge water” into the ocean, which negatively affects sea life as it works its way through the entire oceanic ecosystem. A single cargo ship can produce several tons of oily bilge water daily.

To protect the oceans and the increasingly CO2-filled atmosphere, reducing the shipping industry’s emissions by reducing its reliance on these heavily polluting fossil fuels is essential. Mitigating technologies discussed below, like metal sails, biofuels, and slower shipping speeds can accomplish this. To implement these changes, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) can use enforcement mechanisms like the ones it used to reduce the sulfur content of fuel. Ultimately, however, mitigating technologies are not enough. The world needs to lessen its dependence on shipping if shipping is ever to be carbon neutral.

What is the shipping industry doing to address its emissions?

The IMO and the shipping industry have recognized the importance of reducing shipping’s environmental impact. The IMO, which consists of 175 member countries, including nearly every country with a coastline, has pledged to gradually reduce shipping emissions by cutting 20% of CO2 emissions by 2030 and 70% by 2040 compared to 2008 levels. The IMO’s ultimate goal is to bring shipping emissions to net-zero “by or around” 2050. Critics say this goal is unachievable as the demand for shipping is increasing globally. However, if the industry uses several viable solutions in tandem, the industry could meet its goals.

What could the shipping industry do to reduce reliance fossil fuels?

The shipping industry needs to quickly reduce its existing fuel-oil-burning fleet emissions while transitioning away from engines that burn such lousy fuel. It can do this by adding sails, slowing down, implementing design changes, and changing its fuel mix.

Wind-powered ships

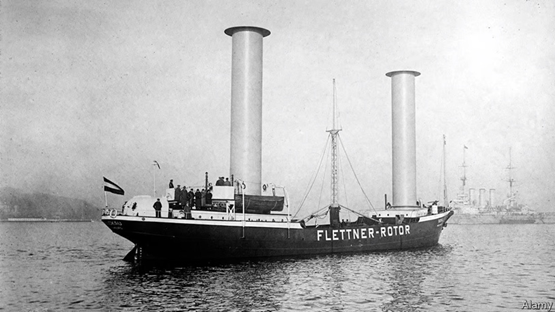

Perhaps the most exciting solution is an old technology repackaged for the modern era: sails. Unlike the merchant ships of the 1700s, most of these modern sails do not use canvas and ropes to harness the wind. Instead, they are made of steel, carbon fiber, or an undisclosed inflatable material. Wind, of course, is a renewable resource, and once the sails are manufactured and installed, they become a fossil-fuel-free source of propulsion. A few different kinds of sails are available: rotor sails, kite sails, and wing sails.

Rotor sails are made of steel and have been around since the 1920s. However, they fell out of use because coal and petroleum-based fuels were cheaper and more widely available, and they are only just now starting to make a comeback. They work by rotating, which causes the wind to travel faster on one side than the other. The wind creates a force that propels the ship forwards. They can cut fuel consumption by up to 30%.

Wing sails operate more like airplane wings than traditional canvas sails. Their curvature forces the wind around them in a way that provides forward propulsion. Such technology has been available for over a decade, and with enough wing sails, no fossil fuels are necessary on routes with good wind currents.

As of last year, only twenty merchant vessels had wing sails. That number is expected to grow to fifty this year, but this has a negligible impact since the world has 55,000 active large container ships. More needs to be done, and quickly, to encourage vessels to install sails.

Alternative fuels

Alternative fuels could fill the gap for routes where the wind is insufficient. However, using most of these fuels requires engine modification, which is a costly and time-consuming process. These fuels include ammonia, LNG (though LNG is a petroleum product, it creates less CO2 than oil and burns without many of the waste products that fuel oil creates), hydrogen, and biofuels. Currently, normal ship engines can burn a blend of up to 20% biofuel, and any blend rate beyond that requires engine modification. Yet the supply of biofuels is not large enough to blend at that rate industry-wide, and industry-wide engine modification has been a slow process.

Increasing efficiency: Slowing down and design modifications

Slow steaming can reduce fuel consumption. A 12% reduction in at-sea average speed leads to an average decrease of 27% in daily fuel consumption. Because ship owners often receive bonuses from the charterers if they arrive early, slow steaming is not currently favored. There are also design efficiencies—hydrodynamic coatings, “duck tails” on the back of ships, regular cleaning of hulls and propellers, and sending compressed air beneath the boat—that make ships more hydrodynamic and fuel efficient. None of these technologies is in wide use for the same reasons that sails have failed to gain widespread installation—upfront costs are too high, and fossil fuels are too cheap.

What is stopping the industry from implementing changes?

Fossil-fuel-reducing sails have been available for over a century, but installation rates are abysmal. Uptake of alternative fuels and other design changes are likewise glacial at best. There are two main reasons that sails and other technologies have not been installed: oil is too cheap relative to the expense of installing green technology, and it is difficult to regulate international waters.

Oil is too cheap

The price difference between fuel oil and installing green technologies is too big for market forces to drive change in the shipping industry, and this is a main reason that merchant ships have not adopted sails. Until oil prices rise significantly or the cost of green tech decreases, ships will not opt to install green technology on their own without policy intervention. A carbon tax, tariffs on imports from ships that use fossil fuels, government subsidies such as low-interest loans for green technology, or higher taxes on oil could all serve to raise the price of using fuel oil and incentivize ship owners to install sails or switch to alternative fuels.

Ship owners have little incentive to find more efficient fuel sources

The way in which ship charters are structured requires the charterer, not the shipowner, to pay for the fuel on a given voyage. The shipowner, however, is the entity responsible for making capital improvements to their vessels. Installing sails or making other significant efficiency changes require taking the ship out of commission, resulting in lost revenue. Further, most of the cost savings from enhanced fuel efficiency would be passed on to the charterer, not the shipowner who made the investment. Though it would be difficult to implement, regulating chartering contracts so that charterers and ship owners had to share the cost of fuel could incentivize ship owners to invest in their vessels’ fuel efficiency.

Regulating international waters is difficult

International waters are inherently difficult to regulate. Ships are often owned by one country but sail under the flags of different countries. In fact, almost half of all merchant vessels currently sail under the flags of Panama, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands. Even though these countries are part of the IMO, they do little to exercise oversight of shipping vessels. They attract vessels to register in their countries with their lax regulation, low taxes, and lack of oversight. Moreover, there is little policing of international waters, making enforcement of international maritime treaties and agreements difficult. Despite these difficulties, there are some ways to enforce international shipping regulations. The United States, for example, has statutes allowing the Department of Justice to prosecute any vessel that has violated international shipping laws and wants to dock in the United States. If more countries were to prosecute lawbreaking vessels in this way, there could be more conformity with international shipping laws.

How can lessons from MARPOL 2020 be used to reduce shipping’s reliance on fossil fuels?

Even though the seas can be difficult to surveil and regulate, the IMO has already successfully regulated shipping fuel with its MARPOL 2020 regulations. Its success provides hope that the same enforcement strategies could reduce carbon emissions.

MARPOL 2020 was a regulation that successfully reduced the sulfur content of fuel oil by roughly 70% starting on January 1, 2020. The countries that were part of the IMO agreed to the change in October 2016, giving the industry several years’ advance notice. It was successfully enforced in a few ways. Member states with ports were allowed to fine vessels caught using High Sulfur Fuel Oil (HSFO) without ridding their exhaust of sulfur. Second, ships emitting too much sulfur failed their inspections and were deemed unseaworthy, which caused them to lose their insurance. Also, many member states banned the transport of HSFO, making it unavailable to would-be users.

In the years before MARPOL 2020 took effect, ships and fuel producers were able to prepare for the change. Thousands of ships installed technology called scrubbers. A scrubber removes sulfur from ship exhaust, allowing the ship to continue to use the cheap HSFO while complying with the sulfur emissions standards. Like installing the modern sails, scrubber installation takes nearly a month and is—in the absence of government incentives—cost-prohibitive. It involves taking a cargo ship off the water to install a scrubber and results in months’ worth of lost revenue for a shipping company.

Refineries installed units that could remove sulfur from the fuel onsite, creating enough Very Low Sulfur Fuel Oil (VLSFO) to supply ships that did not have scrubbers. When the regulation was enacted, the industry did not falter, and fuel prices remained stable. In a similar way, with time to prepare and market incentives, fuel producers could ramp up production of alternative fuel sources.

A similar strategy could be used to implement speed limits and force ships to install sails or other green technology. Sail installation would not take much longer than scrubber installation, and it would be easy to tell from afar whether a ship was using sails, aiding enforcement. Countries would likely be eager to collect fines and fees from non-compliant vessels that dock in their ports, and the threat of being deemed unseaworthy would likely force most ships to adhere to the IMO’s CO2-reduction regulations.

What can an individual do?

The shipping industry does not exist in a vacuum. It exists because there is huge, growing, and insatiable market demand for global trade and overseas goods. The globe’s use of shipping must decrease in conjunction with a shift away from fossil fuels. The demand for shipping is forecasted to grow so much that by some estimates, any benefit of green technology in shipping will be offset by increases in worldwide shipping.

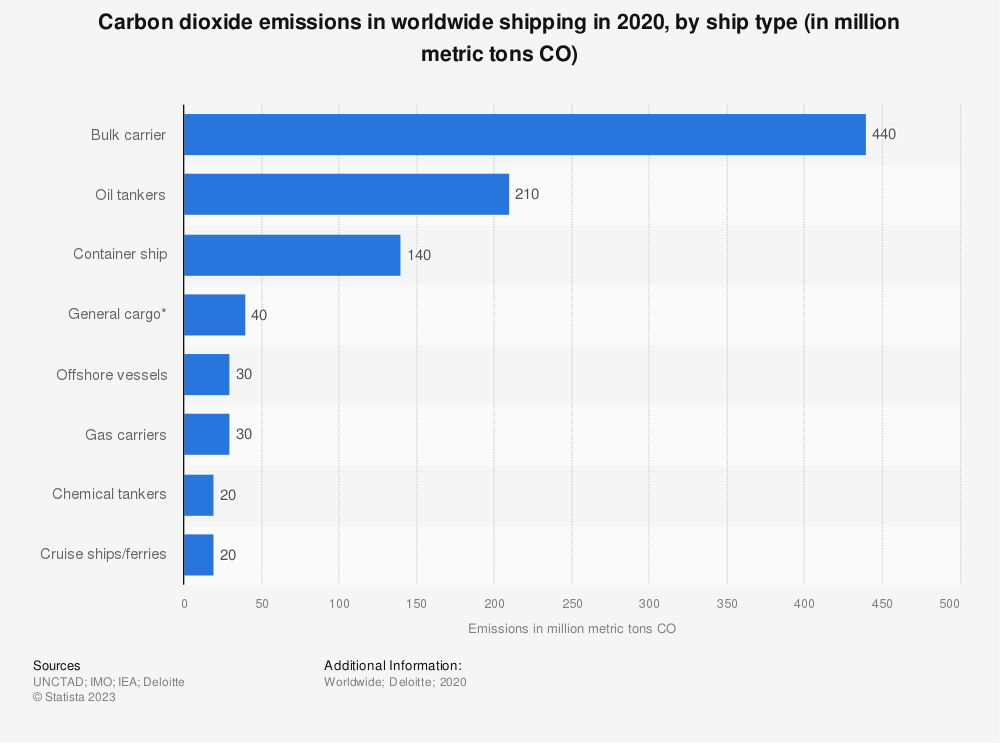

As the bar graph below shows, more than 20% of shipping emissions come from shipping petroleum products themselves. Reducing society’s reliance on petroleum and energy consumption reduces the amount of oil that must travel overseas each year.

Advocacy for worldwide and national reduction in reliance on fossil fuels and systemic changes like the solutions discussed above will make a difference. When paired with stricter maritime law enforcement, policies that would increase the price of fossil fuels, like a carbon tax and decreasing oil drilling, as well as policies that provision financial incentives for ship owners who improve their fleet’s fuel efficiency will increase the rate at which the shipping industry can achieve carbon neutrality.

Individuals can also take a satisfying step in reducing their dependence on shipping by being mindful of their consumption. They can opt for local purchases and locally grown food, which decreases the demand for global shipping. People can also reduce their consumption by repairing, upcycling, and thrifting. Every small effort towards reducing the demand for shipping adds up with time.

Making 55,000 fuel-oil-burning ships carbon neutral may seem like an overwhelming task. There is no simple solution since consumers, shippers, charterers, alternative fuel providers, and government entities have to align and agree to compromises and significant investments for long-term gains. But the wide array of available solutions paired with tried-and-true enforcement mechanisms from MARPOL 2020 provide hope that shipping can soon be far less carbon-intensive than it is today and that the industry can meet its net-zero goal by 2050.

You must be logged in to post a comment.