Over the last few years, misbehavior of corporate executives like Harvey Weinstein, Steve Wynn, Leslie Moonves, and Elon Musk has outraged many people around the world. The misconduct has ranged from the inadvisable to the unethical to the criminal. Almost all of it – when made public – has damaged the executives’ public reputations, diminished the value of their companies’ stock, and raised some serious legal and policy issues.

My recent article, Executive Private Misconduct, in The George Washington Law Review examines this convergence of private lives and public consequences of executive misbehavior. The article puts the legal issues arising from this convergence into the context of greater intolerance for executive private misconduct, as prompted by the unfolding #MeToo movement, shifting social understandings of public and private, and changing corporate social expectations. It also analyzes the core legal tensions in corporate and securities law that have made these issues so difficult to resolve and offers pragmatic proposals for policymakers and executives.

Part of the challenge in dealing with misbehaving business executives is that the two bodies of law and regulation that govern much of American business – state corporate law and federal securities law – were largely designed to address the professional duties of executives and not their personal lives. As such, corporate law principles of fiduciary duties and securities law principles of disclosures were not designed to confront the hard issues and questions raised by executive private misconduct, leading to serious corporate governance tensions and arbitrary practices.

In practice and design, corporate law’s fiduciary duties of care and loyalty, and obligations of oversight generally focus on professional conduct and matters of the firm and its executives in connection with the objective of maximizing shareholder value. What happens in the private lives of company executives has traditionally been understood to be beyond the scope of corporate law. Furthermore, tough legal standards that favor corporate defendants, along with legally permissible insurance, indemnification, and exculpation for corporate directors, minimize the risk of personal liability and provide little incentive for firms to vigilantly police executive private misconduct. However, at a time when the private matters and conduct of executives can have very serious and often public consequences for a company and its investors, corporate law’s shortcomings have become magnified, raising critical questions about the core duties of care and loyalty, and obligations of oversight.

Similarly, in practice and design, federal securities law’s principle of full and fair disclosure generally focuses on the professional affairs of the firm and its executives. What happens in the private lives of company executives has traditionally rested outside the scope of federal securities law, absent some rule or regulation mandating disclosure. In the contemporary socioeconomic and media landscape, however, where private matters and executive conduct can have very serious and often public consequences for a company and its investors, securities law’s shortcomings in this area have become more pronounced and substantial, raising critical questions about the efficacy of longstanding line-item and antifraud material disclosure rules.

These legal gaps and tensions in corporate law and securities law, outlined above, have led to arbitrary and risky practices in boardrooms across America, endangering firm stability and shareholder value. The absence of clear legal guidance and best practices has given companies much discretion to decide how to address executive private misconduct questions on an ad hoc basis, because no two firms or executives are identical. In practice, this wide latitude means that companies can engage in arbitrary and risky corporate governance practices that readily place an executive’s desires for privacy over the interests of firms and shareholders, despite their obligations pursuant to corporate and securities law.

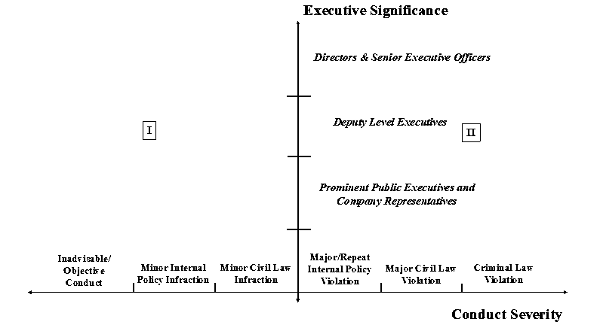

While there are no silver bullets for curing the legal and practical tensions posed by executive private misconduct, there are, however, better ways to address these issues. My article recommends a number of proposals rooted in rethinking and upgrading corporate governance, corporate policies, and corporate purpose in a changing society and marketplace. First, it recommends an original baseline framework for systematically analyzing these issues, built on the intersectionality of executive significance and conduct severity, as illustrated in the figures below:

Figure 1. Baseline Framework

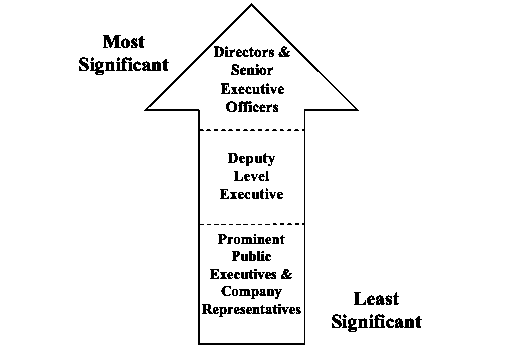

This framework categorizes senior executives into three tiers from most significant to least significant, as illustrated in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Tiers of Executive Significance

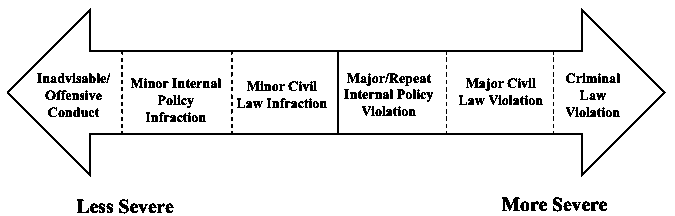

In terms of conduct severity, this framework categorizes misconduct into a spectrum of six broad categories, where three types of conduct are considered increasingly severe and three types of conduct are considered decreasingly severe, as illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Spectrum of Conduct Severity

Such a framework offers a systematic, structured way to analyze and address these issues for corporate boards rather than the arbitrary process that is too prevalent. Applying the framework, matters that fall into Quadrant II—involving more serious misconduct allegations, such as those implicating a potential major civil law or criminal violation—should be disclosed to the board for review and investigation. To the extent such allegations are found to be credible, the company should operate with a presumption of disclosing such allegations publicly via press release and a filing with the appropriate regulatory authorities, like the SEC. On the other side of the spectrum, matters that fall into Quadrant I—involving less severe conduct, like minor civil law infractions, minor internal policy infractions, and offensive conduct—generally should be addressed through the company’s internal human resources systems rather than be elevated to the board or senior leadership level. In practice, this baseline framework offers a pragmatic starting point for systemically rethinking about executive private misconduct. Companies should build on this framework by tailoring a specific guide appropriate for their company’s leadership structure, business models, and internal code of conduct policies.

Second, the article recommends that companies change certain longstanding business practices and policies. In particular, businesses should: (1) operate with the default position of not using nondisclosure agreements for settling allegations involving executive misconduct; (2) use arbitration as an opt-in dispute resolution alternative, rather than as a mandatory step in disputes involving misconduct; and (3) issue an annual, firm-wide report disclosing key statistics on misconduct complaints and incidents. Undoubtedly, the hard work of reform will lie in the actual drafting, implementation, compliance, and enforcement of any new rules and policies. That said, these recommendations can serve as meaningful starting points for that hard work.

Ultimately, executive private misconduct issues are forged in a complex crucible of law, capital, power, and privacy. So long as humans are flawed, there will always be offensive behavior, criminal acts, and discriminatory conduct by executives and others in business. In the end, though, because of the influential role of businesses and their leaders, efforts addressing executive private misconduct can play an important role in creating better workplaces and forming a more just society.

A version of this article was previously featured in the Columbia Law School Blue Sky Blog. The full paper is available for download here.

Tom C.W. Lin is the Jack E. Feinberg Chair Professor of Law at Temple University’s Beasley School of Law. He is also an Academic Fellow at George Washington University’s Center for Law, Economics & Finance. His research and teaching expertise are in the areas of business organizations, corporations, securities regulation, financial technology, financial regulation, and compliance.